Your Cart is Empty

Kevin DeYoung

January 26, 2023

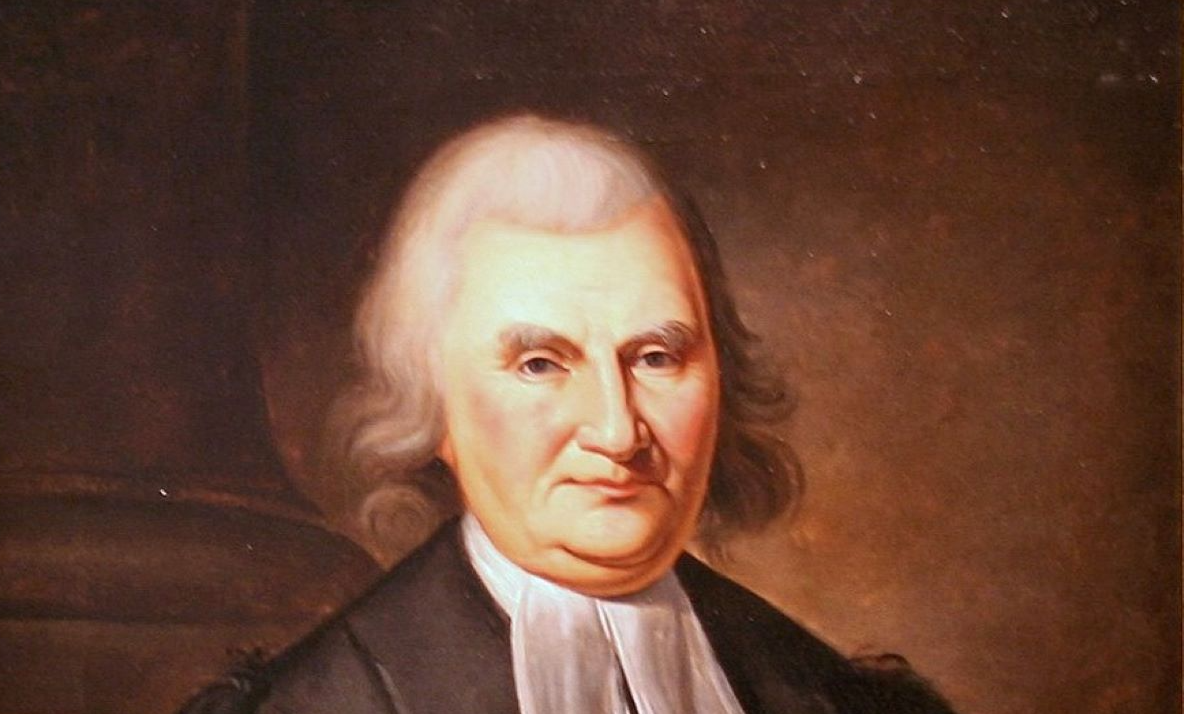

As of the online publication of this essay, Princeton University is still deciding what to do with Witherspoon. The Council of the Princeton University Committee on Naming is forming its recommendation in response to the petition initiated in May 2022 to remove from its place of honor in Firestone Library Plaza between East Pyne Hall and the Chapel the statue of John Witherspoon (1723 – 1794), Princeton’s sixth president who led the (then) College of New Jersey from 1768 until his death 26 years later. This statue, commissioned by the Princeton University Board of Trustees, was dedicated in 2001. The initiators of the petition have cited as reasons for the statue’s removal their beliefs that Witherspoon “participated actively in the enslavement of human beings, and used his scholarly gifts to defend the practice.” One opponent to the proposed removal of Witherspoon’s statue submitted that the petitioners have “a tragic misunderstanding. . . of the full measure of Witherspoon on slavery.” In this present essay, I present new evidence on the duration and nature of Witherspoon’s ownership of slaves. I also briefly note Witherspoon’s connections to other evangelical Christians active in the abolition movement. By reviewing these facts—some of them not mentioned before in any of the secondary literature—I hope to present a fuller measure of Witherspoon on slavery.

In December 2022, I wrote an article opposing removal of the Witherspoon statue. Among the salient aspects of Witherspoon this piece explored were his outstanding service to Princeton, his courageous participation with the founders of our nation as a signer of the Declaration of Independence, his foundational leadership in the Presbyterian church, and, yes, the sad fact that he had owned slaves. This article generated a fair amount of attention, much of it negative. For many people, any defense of Witherspoon is tantamount to defending slavery itself. Of course, that was not the purpose of my article. We all wish slavery had not been present at the American founding, and we all lament that so many great men from that era could not see their own moral inconsistencies (or in some cases, egregious hypocrisies).

At the same time, it behooves us as critical thinkers, and simply as fellow human beings, to try to understand people from the past in their own context and on their own terms. In Witherspoon’s case, this doesn’t mean we justify slavery, but it does mean we must not accept the quick (and misleading) summary that says nothing more than “Witherspoon owned slaves and voted against abolition.” As I showed in my previous article, Witherspoon baptized a runaway slave in Scotland, taught free Blacks at Princeton, believed no man had the right to take away the liberty of another based on a superior power, and longed for the final abolition of slavery in America. As chairman of the New Jersey committee considering abolition, Witherspoon did not oppose abolition. Rather, he believed that laws were already in place to ensure the decent treatment of slaves and to encourage voluntary manumission, and that slavery would soon die out in America. He was, of course, wrong in this last conclusion, but most colonial leaders shared the same assumption. They did not know Eli Whitney’s cotton gin (invented in 1793) would revolutionize the cotton industry and vastly increase the demand for slave labor in the South.

But I don’t need to repeat the facts and arguments from my previous article. What I want to do next in this article is present new information about evidence of Witherspoon’s slaveholding—information I’ve not seen mentioned in any of the secondary literature or included on the Princeton and Slavery Project website. There are two direct pieces of evidence showing that Witherspoon owned slaves: (1) the New Jersey tax ratables, and (2) the listing of his possessions at the end of his life. Each one merits careful examination. Let’s start with the first piece of evidence.

The New Jersey State Archives holds the tax ratables for colonial New Jersey. These are, as the name suggests, records about property and other goods and the taxes levied on these possessions. At the end of 2022, I asked the State Archives if they could send me the relevant tax ratables for the Western Precinct of Somerset County (where Witherspoon’s country estate, Tusculum, was located). At that time, they hadn’t finished scanning all the documents, so I was only able to see enough of the ratables to confirm that the first record of Witherspoon owning a slave shows up in 1780 and that by 1784 he had two slaves. Within the past week, the excellent archivists in Trenton finished scanning the rest of the relevant documents and sent them to me. Here’s what they show: In 1785 and 1786, Witherspoon had two slaves. There is no record for 1787. But there are records for 1788, 1789, 1790, 1791, 1792, 1793, and 1794 (when Witherspoon died). In each year they list Witherspoon as owning zero slaves. After Witherspoon’s death, his wife Ann is mentioned in the tax ratables. No slaves are mentioned in her possession either.

Here is a simplified table of information drawn from the tax ratables (gaps in the sequence indicate no extant records for that year):

| Name | Date | Acres of arable land |

Slaves |

|---|---|---|---|

| John Witherspoon | May 1780 | 500 | 1 |

| John Witherspoon | 1784 | 500 | 2 |

| John Witherspoon | July 1785 | 578 | 2 |

| John Witherspoon | August 1786 | 556 | 2 |

| John Witherspoon | September 1788 | 556 | 0 |

| John Witherspoon | August 1789 | 546 | 0 |

| John Witherspoon | February 1790 | 546 | 0 |

| John Witherspoon | September 1791 | 556 | 0 |

| John Witherspoon | September 1792 | 546 | 0 |

| John Witherspoon | September 1793 | 546 | 0 |

| John Witherspoon | September 1794 | 546 | 0 |

| Ann Witherspoon | September 1795 | 494 | 0 |

| Ann Witherspoon | September 1796 | 211 | 0 |

| Ann Witherspoon | September 1797 | 211 | 0 |

As we can see, Witherspoon did not own slaves—at least as the county assessor counted things—for most of the years he lived at Tusculum. (He moved from the college proper to Tusculum a mile away in 1779.). We don’t know how he acquired a slave in 1780. Did he purchase the enslaved person? Had the enslaved person already been working the property? Was the enslaved person assigned to him by the college? Nor do we know what changed in 1788 (or 1787). Were the two slaves sent elsewhere? Did they die? Were they emancipated? These are questions that probably cannot be answered. What we do know is that according to these records Witherspoon owned one and then two slaves over the course of seven years.

There is another fascinating discovery in the tax ratables. In 1792, 1793, and 1794 there is listed for the first time another Witherspoon (spelled “Weatherspoon” as John’s name also was), with the designation N (1792), then Ne (1793), then Neg (1794)—Neg being the designation for Negro. The persons marked “Neg” always shared a last name with a landowner and were likely servants or slaves who had been recently freed, or slaves who had been given property on their way to full emancipation. This African-American Witherspoon—the first name is spelled differently each year, but it is something like Forton—owned cattle and was listed as a householder.

The presence of a Black man with the surname Witherspoon is an important discovery. We don’t know if Forton was a new slave bought in 1792 because John Witherspoon went blind in both eyes in 1791 and needed new assistance. Or it might be that a new slave (or two) came to John upon his marriage to Ann in 1791, were given a household of their own, and worked for the Witherspoons until John’s death in 1794. Ann Witherspoon’s first husband came from a slaveholding family in York County, Pennsylvania. Perhaps the man Forton (and his wife?) came with Ann and that’s why the two slaves counted at the time of Witherspoon’s death include the curious reference to “until they are 28 years of age,” twenty-eight being the age at which those born into slavery were to set free under Pennsylvania law. Or it could be that in 1787 or 1788 Witherspoon gave his two slaves their own portion of the estate, such that the assessor no longer counted them as slaves in his possession. Perhaps Somerset County only began to designate “Negroes” in the tax ratables beginning in 1792. After 1794, presumably when the widow Ann would have needed help the most, there is no mention of the “Negro” Witherspoon, suggesting that he was free to go where he pleased.

This still leaves us with the fact that two slaves are listed among Witherspoon’s assets at the time of his death. The slaves are nowhere mentioned in Witherspoon’s last will and testament. The will—drawn up on September 15, 1794 and modified on November 11—only stipulates who is to receive portions of his settled estate. No specific possessions are enumerated until after Witherspoon’s death when, on November 28, two appraisers list his possessions and provide a value for every item. This is where two slaves are mentioned.

We can’t be sure how to reconcile the appraisers’ mentioning of two slaves at the time of Witherspoon’s death with the listing of no slaves according to the tax ratables of the same year. There must have been some arrangement which rendered the status of the “Negro” Witherspoon ambiguous. The most likely explanation is that Witherspoon gave his slaves—either in 1787/1788 or upon receiving two slaves through his second marriage—a share of his estate that they might be prepared, in due course, to live in full freedom on their own. We know from Witherspoon’s Lectures on Moral Philosophy and from his work on the New Jersey committee mentioned earlier that Witherspoon was in favor of abolition, but that he also believed that moving too quickly could be dangerous for society and “make [slaves] free to their own ruin.” He was, in other words, a consistent proponent of gradual abolition.

How should we put all these pieces together? My best guess is that two slaves (husband and wife?) came with Ann Dill in her marriage to John Witherspoon, that they were considered Witherspoon’s assets by the assessors executing his will, but that the slaves were, in another sense, free persons and were listed as such in the tax record. The reference to “28 years of age” in Witherspoon’s will gives credence to the suggestion that the slaves would be free from all obligations at 28 years old (at the latest) in keeping with the 1780 Pennsylvania statute. If two Black persons came as a part of Ann’s property, it seems they were treated as free Negroes in their own household, but also had some sort of agreement (willingly or unwillingly we don’t know) to remain as servants so long as John was alive and needed assistance. In 1795, Ann had 494 acres in her possession, but this went down to 211 acres the following year, so she did not continue to maintain their estate on the same scale.

The best example of Witherspoon’s thought on slavery and how to end it probably comes from the statement made by the Synod of New York and Philadelphia (i.e., the Presbyterian church) in 1787 and later reiterated in 1794. We should not forget just how revered Witherspoon was among his fellow Presbyterians. He was appointed to almost every important committee in the early years of the national Presbyterian church. He drew up many of the church’s foundational documents and was given the honor of preaching the opening sermon at the first General Assembly in 1789. At that first Assembly, there were 188 ministers present, 97 of whom were from Princeton, 52 of those being Witherspoon’s former pupils. Given his stature as senior statesman and as the personal mentor for over a quarter of the commissioners, the statement on slavery in 1787 undoubtedly reflected Witherspoon’s own beliefs and may have been drafted by him.

Here, in full, is the statement on slavery adopted by the Presbyterian church in 1787:

The Synod of New-York and Philadelphia do highly approve of the general principles, in favor of universal liberty, that prevail in America; and the interest which many of the states have taken in promoting the abolition of slavery. Yet, inasmuch as men introduced into a servile state, to a participation of all the privileges of civil society, without a proper education, and without previous habits of industry, may be, in many respects dangerous to the community. Therefore, they earnestly recommend it to all the members belonging to their communion, to give those persons, who are at present held in servitude, such good education as may prepare them for the better enjoyment of freedom.

And they, moreover, recommend, that matters, wherever they find servants disposed to make a proper improvement of the privilege, would give them some share of property to being with; or grant them sufficient time, and sufficient means, of procuring, by industry, their own liberty, at a moderate rate: that they may thereby be brought into society, with those habits of industry, that may render them useful citizens.

And, finally, they recommend it to all the people under their care, to use the most prudent measures, consistent with the interest and the state of civil society, in parts where they live, to procure, eventually, the final abolition of slavery in America. (Emphasis in original)

This long statement may give us the fullest and clearest explanation of Witherspoon’s views on slavery and abolition. He did not think men should be forced into slavery, but once already enslaved, he did not think immediate emancipation would be good for society or good for most slaves. He believed slaves should be educated and treated humanely. He favored abolition, but gradually and eventually. Toward that end, Witherspoon encouraged masters to give slaves a share of property, thus allowing them to be better prepared for freedom. It seems that Witherspoon likely practiced what he preached by making “Forton Weatherspoon” a householder of his own and giving him the opportunity to be fully emancipated, which he appears to have been shortly after Witherspoon’s death.

Many Americans know of John Newton (1725 – 1807), or if they don’t know of Newton directly, they’ve heard his famous hymn “Amazing Grace” (1773). What many may not know is that Newton was, before his conversion to Christianity, a participant in the Atlantic Slave Trade, first serving on a slave ship in 1745 and continuing work on slave ships and investing in the slave trade for many years. Although Newton was “awakened” to God and his sin in 1748, he wrote in 1764 that he was not “a believer in the full sense of the word, till a considerable time afterwards.” In 1764, Newton began service as an Anglican clergyman. He moved to a church in London in 1780, eventually becoming one of the leading evangelical ministers of his day. In 1787, Newton published his Thoughts upon the African Slave -Trade (1787), in which he confessed his own complicity in the slave trade and called for its abolition.

Newton was one of the most important influences in the life of William Wilberforce (1759 – 1833), the acclaimed British leader who committed his life to the abolition of the slave trade. Following an evangelical conversion in 1785, the young Member of Parliament doubted that he should remain in politics. Witherspoon sought out Newton for counsel, who urged him to continue and “serve God where he was.”

While it would be too much to claim that Witherspoon was a pivotal in the lives of Newton and Wilberforce, it is worth noting that the three evangelicals were connected at various points. In 1791, the College of New Jersey, under Witherspoon’s leadership conferred an honorary degree upon Newton. No doubt, the school sensed a spiritual connection with Newton, but the degree also suggests implicit support for Newton’s role in opposing the slave trade. Both Newton and Wilberforce commended Witherspoon’s theological writings, especially his Treatise on Regeneration (1764). Newton said it was the best book he had read on the subject, while Wilberforce, for his part, recommended the book often, gave it away to friends, and penned a complimentary essay in 1823 for a new edition of the work. If Witherspoon had been seen as a friend of slavery and an enemy of abolition in his own time, it is unlikely that Newton and Wilberforce would have thought of him so highly and praised his work so unreservedly.

In all of this, we can still wish that Witherspoon had moved more quickly to free slaves in his own life or made the case for final abolition with more urgency. Indeed, New Jersey would become the last northern state to abolish slavery, doing so only in 1866, a year after the Civil War ended. But considering the totality of his teaching and his personal example on the issue of slavery, we ought to question any assessment that makes Witherspoon out to be someone deeply enmeshed in slavery throughout his life or in favor of the indefinite perpetuation of slavery. There is little doubt that Witherspoon was more enlightened on the issue of slavery than many of his generation, and less personally complicit in the evils of slavery than men like Jefferson, Madison, Washington, Franklin, and many of our country’s most celebrated founders.

Witherspoon was respected in his day as a great theologian, an exemplary college president, and an “animated son of liberty” whose leadership and sacrifice did much to advance the cause of the American Revolution and to establish the governing principles of the new republic. Even on the issue of slavery—though compromised by our standards—he showed himself to be moving in the right direction and called others to the same. With eyes wide open to his faults, Witherspoon’s legacy deserves to be commemorated—by the Scottish, by Americans, by Presbyterians, and, yes, by Princetonians too.

The last two years have seen a dramatic increase in the scrutiny of free speech and academic freedom on university campuses, largely in response to the protests that followed the Hamas terrorist attack on Israel and the Israeli invasion of Gaza. There has been important progress during this period that bolsters awareness of the importance of free speech and academic freedom principles.

However, progress on these core values will mean little if there is not a major effort to address a pressing long-term and deeply embedded problem – the almost total lack of viewpoint diversity among faculty at many universities.

On Jan. 5, the University released its annual Report of the Treasurer. Following a tumultuous year for higher education across the country, the report emphasizes the University’s lab partnerships with federal departments, close ties to active-duty soldiers and veterans, and involvement in AI and public service.

The report, entitled “In the Nation’s Service,” comes after approximately $200 million in research-specific funding was suspended last year by the Trump administration, then partially reinstated over the summer.

Princeton is an undemocratic place. Its premier open deliberative body, the Council of the Princeton University Community (CPUC), is fraught with attempts to filter legitimate dialogue and debate between various campus interests. Indeed, as my colleague Siyeon Lee argued last fall, CPUC meetings “mostly functioned as a Q&A, the decision already made, and the damage already done.”

However, in just under two weeks, at the upcoming Feb. 9 CPUC meeting in the basement of Frist Campus Center, the University community — students, faculty, and staff — will have a rare opportunity for unfettered access to University President Christopher Eisgruber ’83.