Your Cart is Empty

PFS Editorial

Much of the debate over the possible removal of the statue of John Witherspoon from the Princeton campus is based on information about Witherspoon’s involvement with slavery and the debate over abolition contained in the University’s Princeton & Slavery Project (the Project). It is now clear that this information is both incomplete and misleading. In a March 1 open letter to President Eisgruber and the Princeton Board of Trustees, PFS called for the Project’s Witherspoon materials to be revised to reflect critical new information that had just come to light. There has been no change. Now, a new and important analysis by Bill Hewitt ’74 of the Project’s content on Witherspoon makes the case for reassessment even stronger.

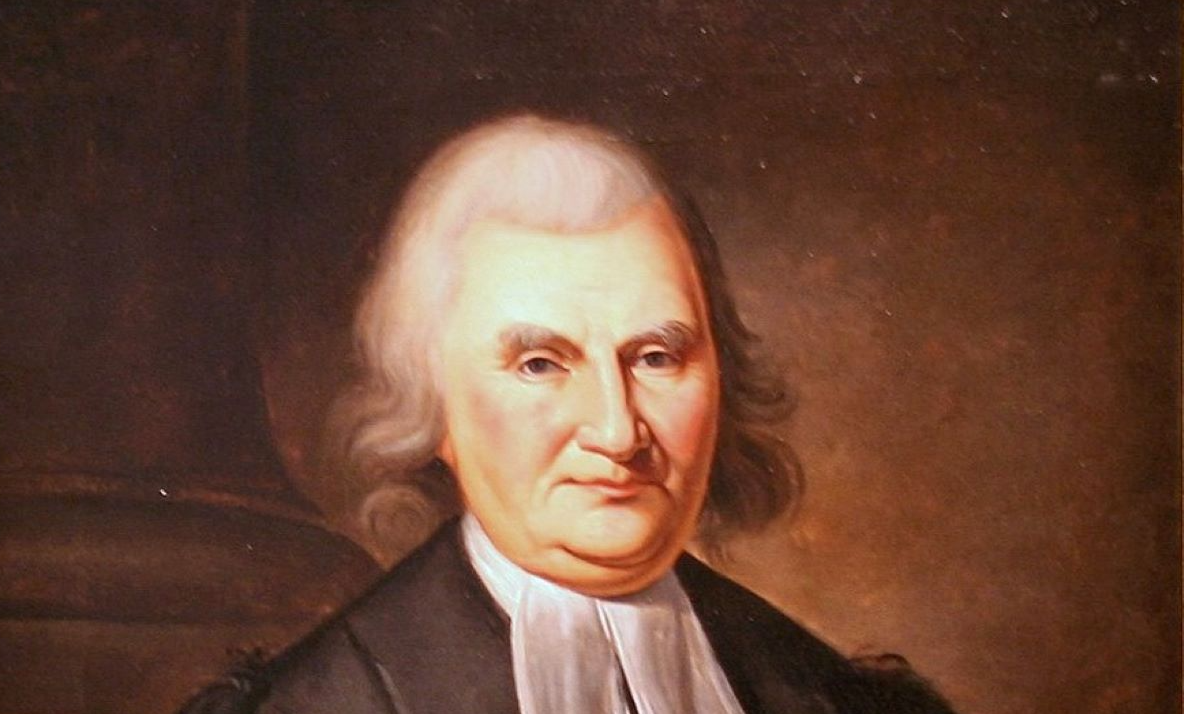

John Witherspoon was an important figure in the founding of our country – a signer of the Declaration of Independence, a contributor to the Articles of Confederation, and an active member of the Continental Congress. He also probably was the most important figure in the creation of Princeton as a great university, saving it when it was near bankruptcy. Princeton owes to Witherspoon’s legacy and to the history of the university and of the country, a fuller and more accurate picture of the man.

Instead, the Princeton & Slavery Project’s essay on Witherspoon has portrayed Witherspoon in a misleadingly harsh light, as a man who “contributed to the United States becoming a cradle of slavery from its very founding,” who “denied enslaved people their humanity and defined them simply as another form of property” and who “retained ownership over” his two slaves, showing “an unwillingness to subject himself to the same moral philosophy he advocated to his students.”

As Hewitt’s essay argues, the historical facts, on the contrary, show that Witherspoon consistently advocated for slavery’s gradual abolition, which, he and many others believed incorrectly would die out before long. They also suggest that he “likely practiced what he preached by making [his slave] ‘Forton Weatherspoon’ a householder of his own and giving him the opportunity to be fully emancipated, which he appears to have been shortly after Witherspoon’s death.” (See Kevin DeYoung, A Fuller Measure of Witherspoon on Slavery, published by PFS.) Even the Project acknowledged that Witherspoon had baptized a runaway slave in 1756 while serving in Scotland as a Presbyterian minister and tutored two freed African men in 1774 while serving as Princeton’s president.

PFS’s March 1 letter was based on important new information obtained from the New Jersey Archives tax records by DeYoung, an authority on Witherspoon. The tax records show that it is highly likely that Witherspoon had moved as of 1788, six years before his death, to emancipate his two slaves and to provide them with the economic means to succeed, which was in keeping with his stated philosophy on the process of emancipation.

Hewitt’s essay, which appeared on April 18 in the Princeton Tory and which PFS has shared on its website, demonstrates that, even before the new information discovered by DeYoung, the Project’s depiction of Witherspoon was both incomplete and misleading in a number of respects, and repeatedly twists facts to assume the worst about his motivations. For example, the Project failed to mention the leadership of Witherspoon in the 1787 Presbyterian Church’s adoption of a resolution for the abolition of slavery. And the Project based its sweeping claim that he “denied enslaved people their humanity” solely on a two-sentence analogy attributed in Thomas Jefferson’s 1823 autobiography to Witherspoon’s untranscribed statement in a 1777 debate about taxation of horses and of slaves.

Hewitt ends his essay by saying that the Princeton & Slavery Project’s “Witherspoon and Slavery” essay “fails the ‘rigorous academic standards’ President Eisgruber heralded in an announcement in 2017 regarding the Project’s findings. [The]Project published this flawed and damaging essay . . . and allowed it to stand uncorrected for over five years. … An institutional failure of this magnitude, duration, and gravity cannot be dismissed as the result of a single individual’s mistakes. Princeton must address this fiasco of profound proportion.”

The Hewitt article is an important contribution to the discussion and should be given serious consideration, as should his recommendations.

The shooting at Brown is deeply tragic. But it is not the time for mere thoughts and prayers. It hasn’t been for decades. As another Ivy League university, this moment calls for Princeton to stand in solidarity with the victims of the Brown shooting by pushing for significant reform to fight violence. University President Christopher Eisgruber ’83 is uniquely equipped as the past chair and active board member of the Association of American Universities (AAU) — an organization with a precedent of condemning gun violence — to lobby for gun reform policies on the national and state level.

A discussion about Fizz and the role of social media in our discourse took place at Princeton University on December 3rd, 2025, hosted by the Princeton Open Campus Coalition (POCC) and funded by Princetonians for Free Speech (PFS), While the discussion has been lauded as an example of what can come about through open and civil exchange of ideas, several questions remain worth considering. What is the place of anonymous speech in our society? Should someone take responsibility for the things they say? Or has our public discourse been hollowed out by social media to the point where online commentary should be considered performative?

Tal Fortgang ‘17

When Princeton President Christopher Eisgruber spoke at Harvard on November 5, 2025, he expressed what to his detractors may have sounded like an epiphany. “There’s a genuine civic crisis in America,” he said, noting how polarization and social-media amplification have made civil discourse uniquely difficult. Amid that crisis, he concluded, colleges must retain “clear time, place, and manner rules” for protest, and when protesters violate those rules, the university must refuse to negotiate. As he warned: “If you cede ground to those who break the rules … you encourage more rule-breaking, and you betray the students and scholars who depend on this university to function.”